The Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) have been working to strengthen and modernize regulations implementing the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). This joint effort reflects the first significant modernization of the CRA in about a quarter century.

Let’s take a look back at the CRA’s past, including the historical conditions in the nation that inspired it and shaped its implementation.

1934–1962

For most of the 20th century, federal initiatives subsidizing homeownership excluded Native American households and households of color. From 1934 to 1962, for example, 98 percent of federally backed home loans from one program went to white homeowners.

1934–1962

1935

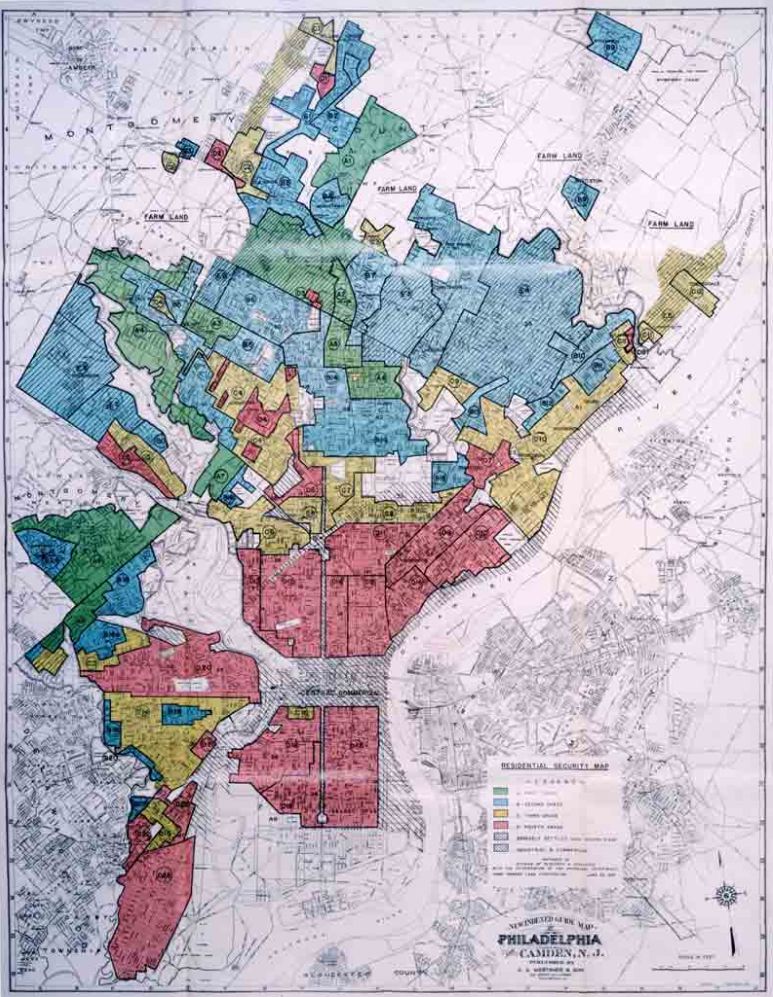

Residential Security Maps

The neighborhoods described as high risk were “redlined.” But the maps’ definition of risk was defined by prejudice, not just actual creditworthiness. Applicants’ nations of origin, their skin color, and other irrelevant characteristics were also factored in.

1935

Residential Security Maps

Federal Reserve researchers have credibly linked redlining to long-term impacts. Redlined neighborhoods are more likely to negatively influence their residents on labor market outcomes, incarceration, and credit scores. People living in these neighborhoods are also less likely to own a home and more likely to experience racial segregation. Redlining’s legacy is even correlated with higher COVID-19 infection rates.

1956

In 1956, Congress passed the Bank Holding Company Act. As a result, banks or bank holding companies would need to demonstrate their responsiveness to community needs before the Federal Reserve would approve consolidation with other financial institutions.

Supportive policymakers devised the legislation in part because of a concern that larger banks, or bank chains, could replace local institutions without adequately providing for the continuation of services to local communities.

Without this regulation, banks could also use bank holding companies to pursue lines of business that could threaten the stability of the banking sector.

1956

1962

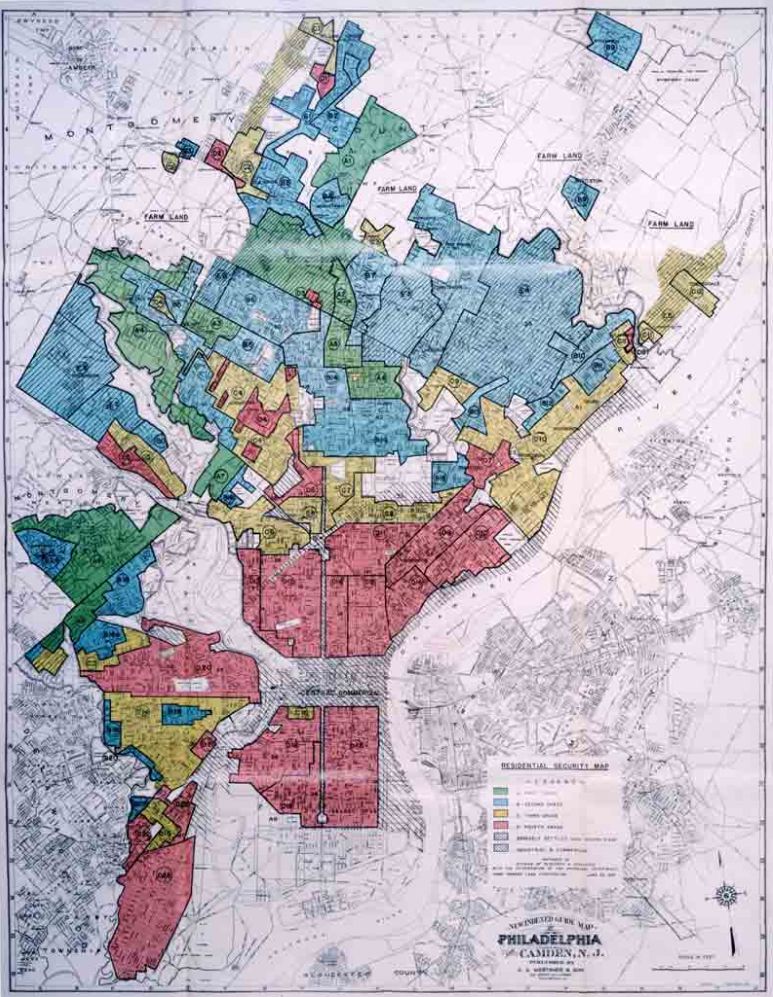

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued an executive order making it unlawful for federal agencies to allow or promote racial discrimination within housing assistance programs.

Photo credit: Robert Knudsen. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

1962

1968–1975

A series of fair lending laws was passed, including the Fair Housing Act and Equal Credit Opportunity Act. These prohibited certain racial, gender, and other forms of discrimination in residential real estate, banking services, and credit transactions. For the first time, Congress would also require lenders to track data on mortgage loans.

Photo credit: Fair housing protest in Seattle, Washington, 1964. Jmabel/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-ND

1968–1975

Their enactment did, however, give regulators some new tools. They could now identify and sanction some of the worst manifestations of discrimination in lenders’ providing access to capital.

Community advocates, policymakers, and economists argued that people in low- and moderate-income neighborhoods still struggled to access credit despite the fair lending laws. In service of this assertion, Congress designed the CRA to evaluate banks’ efforts to meet the credit needs of all people in their communities.

The CRA would not require banks to take undue risks to serve anyone.

Regulators would develop criteria for exams that would assess whether lenders’ processes for extending credit excluded any neighborhoods in their market.

Some of these initial criteria are still in use today. Over time, CRA exams would change, as would activities the Fed undertook to encourage relationships between lenders and community organizations.

Photo credit: President Carter signing the Community Reinvestment Act on Oct. 12, 1977. (Jimmy Carter Library/National Archives and Records Administration)